We’re hungry for good news. The coronavirus pandemic doesn’t leave much room for optimism, but in recent weeks the confinement measures taken in many parts of the world have at least had an encouraging side: Pollution is reduced in many countries of the world.

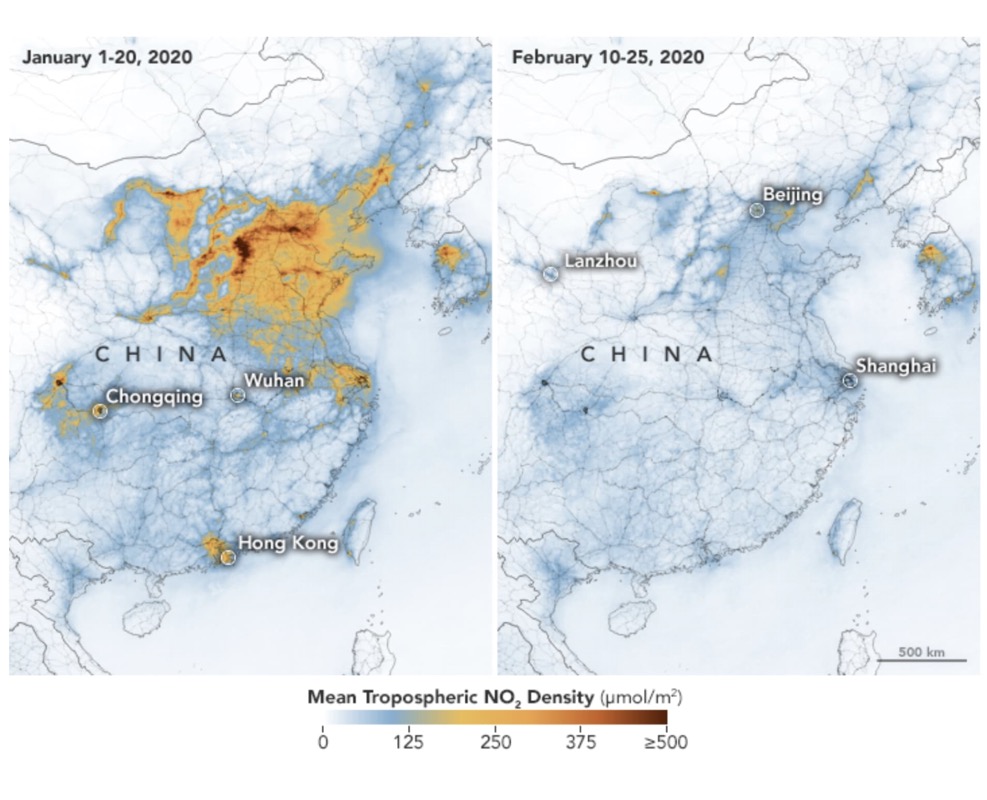

The Wuhan region in China, where the virus first appeared, was also the first to impose a quarantine to stop its spread. During the initial weeks of the restriction on mobility, a photo from NASA showed the precipitous drop in air pollution and in the level of nitrogen dioxide (NO2), a gas mostly generated by traffic and factories.

The NO2 levels were also reduced in other parts of the country. This drop coincided with not only the period of forced confinement, decreed in Wuhan and followed in other parts of China, but also with the dates when the country, and other parts of Asia, celebrate the Lunar New Year. Nevertheless, even though every year NO2 levels drop for this reason, the decline this year was especially significant.

Image credit: Josh Stevens / NASA Earth Observatory

In the middle of March, the European Space Agency made public the satellite images of air contamination in the north of Italy between January and March of this year, much of it coinciding with the quarantine imposed by the Conte government. Just as happened in China, the NO2 levels clearly dropped in comparison to the same period in previous years.

In Spain, data from the Ministry for the Environment show a drop in the levels of nitrogen dioxide in Madrid and Barcelona of 68% and 65%, respectively, in comparison with the previous week. According to Ecologists in Action, the reduction of NO2 in Spain as a whole was around 64%. This data coincides with the drop in automobile traffic in Spain, by an average of 60% with respect to the same period in previous years.

Although Greenpeace observes that this drop in contamination may have been favored by the presence of the DANA, a period of weather instability that we underwent throughout Spain during the first few days of quarantine.

Measures to restrict the movement of people and vehicles are being extended to more and more places around the world. And in all of them, the effect on levels of air pollution can be seen. In Buenos Aires, where confinement began last 20 March, measurements taken in the city over the past few days show a drop of up to 50% in comparison to the same period last year.

It’s obvious that the quarantine has changed cities, and not just in the quality of their air. Their streets are different without people or vehicles.

Images of Venice, in which it is possible to see the bottom of the canals for the first time in years, have gone viral. There are photos of wild animals in the city centres: they are taking advantage of the absence of cars and pedestrians. Deer in the Japanese city of Nara, wild boar in Barcelona, and peacocks in Madrid are just a few examples of this. Life on the highways has also changed: practically their only users are the lorry drivers bringing food and products to the cities.

But what will happen when things get back to normal? Analysts like Lauri Myllyvirta, of the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air in Helsinki, are not optimistic. In an interview for Business Insider, Myllyvirta sees a certain similarity with what happened during the financial crisis of 2008, especially in China, when there was a similar reduction in contaminating air particles in several parts of the country due to a drop in industrial production.

In his opinion, once the pandemic is over China will try to meet its economic objectives for 2020 by ramping up production levels, which will cause new increases in air pollution, just as happened a decade ago.

To all this must be added a more than probable progressive increase in traffic in the cities and on the highways, once the quarantine period is over. As public and private transport get back to normal, the levels of NO2 from traffic will again rise. The current environmental improvement may become a mere anecdote, because we won’t take advantage of it to think about mobility. Will we be capable of making more rational and sustainable use of automobiles after this experience? And if we can’t maintain these current improvements in air quality, will we at least be able to keep the air from reaching those contamination levels before the COVID-19 crisis?