To peer into the future we sometimes just have to go back to the past. It’s kind of that way with the electric car. While many people see it as the great hope for a more rational and sustainable mobility, the electric car is not a futuristic invention. Our ancestors already had it.

As long ago as the first half of the 19th century the first prototypes of electric motors appeared, like the ones built by the Hungarian Ányos Jedlik (1828), the American Thomas Davenport (1834), the Dutchman Sibrandus Stratingh and a Scot, Robert Anderson (1839).

At the start of the 20th century, this kind of vehicle was becoming a favorite for urban transport in many European and US cities. Taxi fleets in some of these places, like businessman Walter C. Bersey’s popular ‘hummingbirds’ in London (so called because of the characteristic buzzing sound their engines produced), used this technology.

Nobody could have predicted that just a few years later they would be forgotten for decades. The discovery of new petroleum reserves, along with the mass production of cars promoted by Ford, made gasoline engines a much cheaper option. And a much faster one, which made them more attractive, especially in the case of longer trips.

So attractive, in fact, that during the past century emissions from fossil fuels burned by vehicles have contributed to a large degree to the fact that just a few months ago there was a new historic record for CO2 concentration in the atmosphere.

This unsustainable environmental situation seems finally to have convinced governments and the auto industry of the need to make a firm commitment to electric transportation. But to finally achieve this, and consolidate the use of this kind of vehicle in both urban and inter-urban transport, requires what many people are calling a change of paradigm.

Among other aspects, it means developing a recharging infrastructure capable of guaranteeing energy for all these vehicles on all their routes. And regarding this point, the large petroleum companies are especially relevant. Some of them, far from seeing electric cars as a threat, have converted part of their business to meet the new challenge of electric cars.

That’s the case with Shell: by buying the New Motion firm, it has set up 150,000 recharging points in 35 European countries.

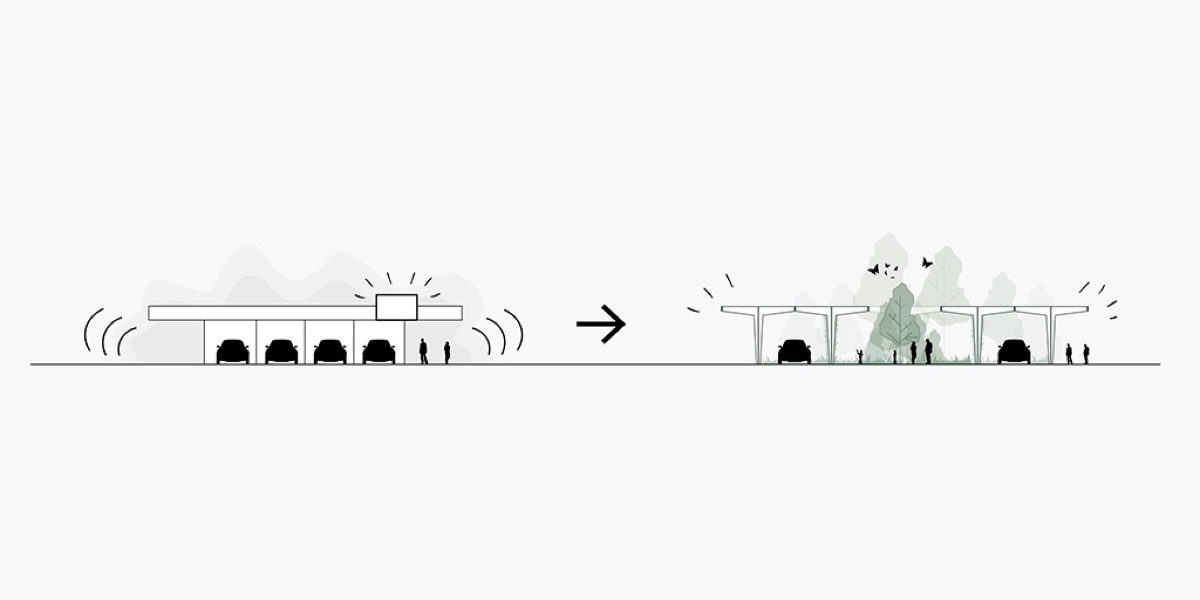

As providers of clean energy, some of these modern electrical charging stations have shown, from both their conception to their design, their commitment to sustainable energy. This is the aim of the rapid-recharging service stations that the E.ON Drive & Clever firm plans to set up on Scandinavian motorways.

Designed by the Danish studio Cobe, they aim to become a “green oasis” that even recharges the energy of the drivers: “Energy and technology are ecological, and so we wanted that to be reflected in the architecture, materials and concept,” says Dan Stubbergaard, an architect and founder of Cobe. “So we designed a charging station with sustainable materials, to be located in clean, calm surroundings with trees and plants that will give travelers some extra attention.”

Re-charging while moving

The industry is especially interested in improving the speed of recharging, which, along with the high cost of these vehicles, is one of the aspects that still discourage drivers from buying these cars. But even at the ultra-rapid recharging points it’s still not possible to do this as fast as at conventional service stations.

But there’s an alternative to waiting the usual five to seven hours to fully recharge a battery: do it while the vehicle is moving. For some years now, this has been tested through what’s known as induction charging.

The system, based on the principle of electromagnetic induction, required the installation in the road of some coils that emit electricity. When the vehicle passes over them, it creates a magnetic field capable of generating current in another coil that will recharge the battery without the need to be in contact with the vehicle.

In 2017, Renault carried out a test on a special track in Satory (France). Two Renault Kangoo Z.E. cars recharged their batteries with up to 20 kWal when driving over it at 100 km/h.

More recently, the Israeli company ElectReon carried out tests on the Swedish island of Gotland over the course of a week on a stretch of road with a 40-ton electric truck.

Although during these first tests with such a large vehicle the system did not achieve maximum performance (the truck did not exceed 30 km/h and the transfer did not exceed 45 kW), the system will be installed in part of that same highway. It is hoped that in the coming months more coils will be placed under the pavement along the whole route to serve a new fleet of electric buses.

Sweden is also the scene of the eRoadArlan project. In this case, the transfer of energy is produced by conductive technology, which makes it necessary to adapt not only the road but the vehicles that drive on top of it. They should have a mobile arm that, when it detects the rail installed in the highway, lowers until entering into contact with it. A system that, as detailed in the La Vanguardia newspaper, is reminiscent of the popular Scalextric slot car racers.

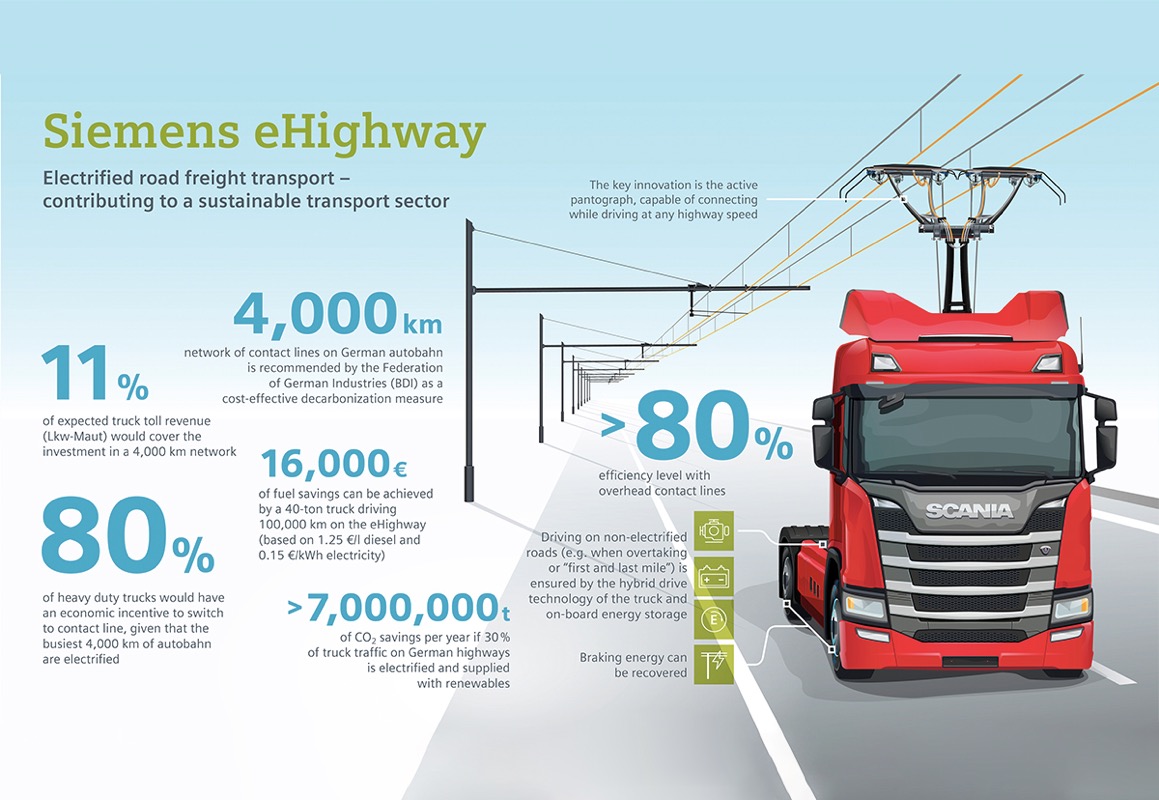

In the project called Elisa, led by Siemens and put into operation on the A5 motorway in the State of Hessen (Germany), contact between the road and the vehicle does not come at ground level but above the vehicle. For the moment, only a certain kind of hybrid truck can use this system, which is similar to that of tramcars.