Questions hover over plug-in hybrids

A report from the European Commission questions the technology of these vehicles, which carry the Zero-emission mark but triple the approved emissions

For a few years now, the choice of vehicle has had a new variable: the type of propulsion the engine will have. The choice was easier to make when the most you needed to take into consideration was whether to use gasoline or diesel. Today, options have multiplied and the range ranges from thermal engines, that is, gasoline, diesel and liquefied or compressed gas; hybrids, either plug-in or not, and 100% electric.

Depending on the type of engine and the fuel that powers our vehicle, and the degree of pollution, the General Directorate of Traffic (DGT) launched environmental badges in Spain in 2016. Other countries such as Germany, Austria, Denmark and France also classify their vehicle fleet this way.

These badges have the objective, according to the DGT’s own description, “to positively discriminate against the most environmentally friendly vehicles and to be an effective instrument at the service of municipal policies, both restricting traffic in episodes of high pollution, and promotion of new technologies through tax benefits or benefits related to mobility and the environment.”

Low emission zones

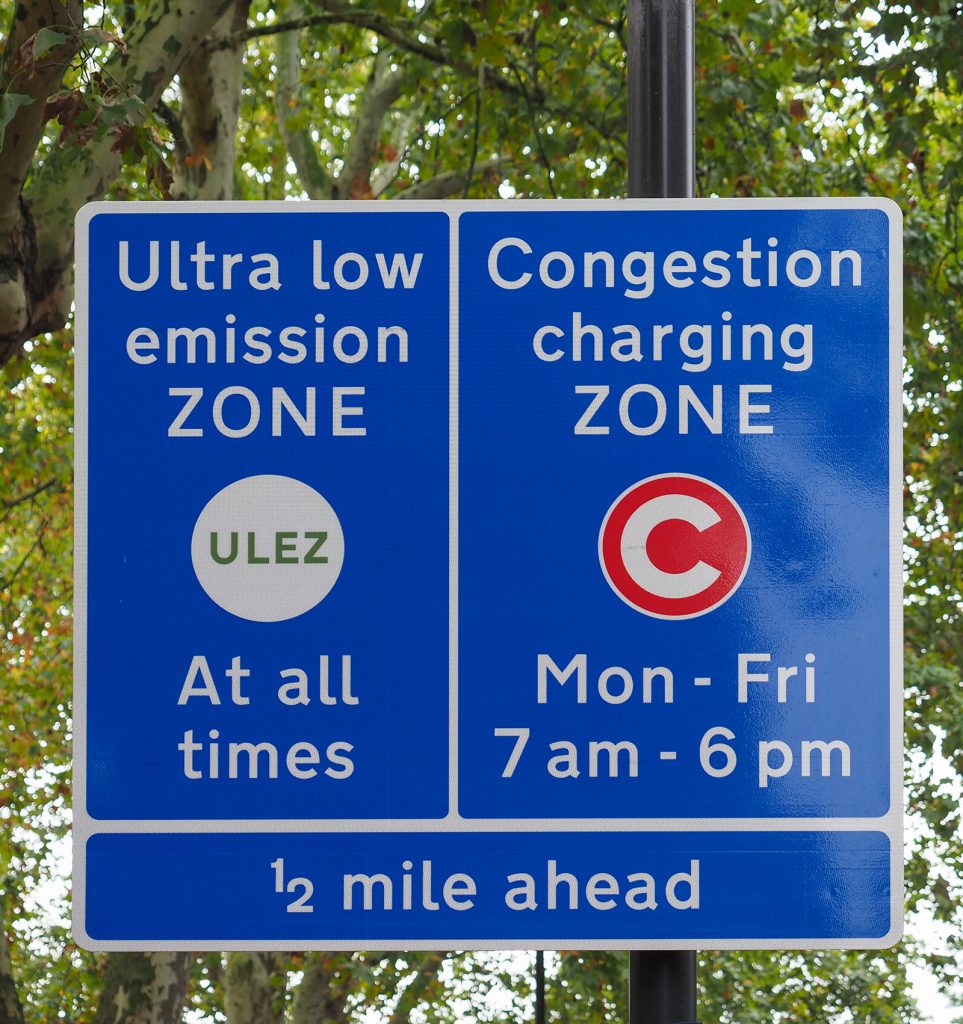

Some large capitals around the world, in fact, already restrict the circulation of vehicles based on their degree of pollution, not only in specific episodes of high pollution, but permanently. They have done this through the declaration of low-emission zones, into which only the cleanest vehicles can enter. This is the case of Spain, where the law requires the establishment of these zones in all cities with more than 50,000 inhabitants. In fact, they have already been launched in several capitals. Most of them, however, have not yet established and regulated them.

In the rest of Europe, some studies, such as those from the Clean Cities campaign, indicate that next year there will be more than 500 low-emission zones across the continent, which implies a growth of more than 40% in the last five years. One step further are the zero emission zones, which only delivery vehicles with non-thermal technology can access, and which already exist in Oxford and London (United Kingdom) and some cities in the Netherlands.

The roadmap for the establishment of these restricted traffic zones is for low emission zones to become zero emission, within the path of climate neutrality objective: 55% less in 2030, and 100% less in 2050. Taking into account that road transport is responsible for a fifth of greenhouse gas emissions in the European Union, and that, of this fifth, 70% come from light vehicles, a few million tons of CO2 will not be pumped into the atmosphere every year.

There are many ways to discourage the use of private vehicles in cities to reduce the emission of greenhouse gasses that accelerate climate change. There are environmental labels and restrictions on certain types of vehicles, but they are not the only ones. New York seems to be following London’s example, with the establishment of tolls to access the congested areas. The measure was to come into force on 30 June of this year, but has not yet been implemented.

Hybrids that don’t match the data

With the global horizon of restrictions on access by private vehicles to the central areas of small, medium, and large cities, people really think about the possibility of their vehicle being certified as low emissions. Hence, electric vehicles or vehicles with hybrid technology, between electric and thermal propulsion, have become popular. Global sales, according to data from the Global Electric Outlook study by the International Energy Agency (IEA), soar by up to 35% annually.

However, a report from the European Commission published in March of this year has put the target on the efficiency, in terms of emissions reduction, of vehicles with plug-in hybrid technology. After analyzing more than 600,000 vehicles of this type, it has detected that they triple the promised emissions and are even more polluting than vehicles powered by a thermal engine.

These verifications have been given on the real use of users with fuel consumption control devices, which has shown that CO2 emissions are 3.5 times higher than those declared in the datasheet, so they emit 100 grams per kilometer of this gas harmful to health and the environment. The disparity also weighs on the wallet, since the same study reveals that consumption increases by four liters of fuel every 100 kilometers.

Diesel and gasoline cars and vans with exclusively thermal engines are not immune to deviations between approval and actual consumption measured by this European Commission report. In these cases, the mismatch is 20%, a lower percentage than in plug-in hybrids.

Why does the deviation occur in the real performance of plug-in hybrid technology, which, in Spain, allows you to bear the 0 emissions badge if the range of the electric motor exceeds 40 kilometers? Apparently, it is about the use made by drivers who, when purchasing the plug-in hybrid, are looking, above all, for a car that can access any part of the city. That is, they do not charge the electric motor of their car and only use the thermal one, with the addition that, in these cases, due to the weight of the set, they are less efficient vehicles than conventional thermal ones.

With this in mind, the European Commission will modify the way vehicles are approved starting next year to better adjust the badges awarded to each technology, with the aim of adjusting the measures to reality. Any change in the consideration of these technologies to obtain the different badges can affect tens of thousands of people, who bought a –generally more expensive—vehicle, to save fuel, reduce CO2 emissions and be able to circulate freely on the roads in low- and zero-emission zones.

Write: Rafael Honrubia