Whether to avoid traffic jams, to reduce pollution or to reduce travel time, cities are looking at ways to change the transportation ecosystem and improve communications.

From Nevada to Madrid, invented by a tycoon or proposed by a political group, transportation modes are in the spotlight. It might involve imagining science fiction futures or planning for sustainable urban planning. The winners are those who advocate for an approachable city and those who are trying to find a solution by drilling into the subsoil.

That’s the proposal of Elon Musk, head of Tesla and owner of the social network Twitter: in Las Vegas, he has implemented his idea against traffic problems. “Traffic is driving me crazy. I’m going to build a tunnel-boring machine and start digging,” he wrote in December 2016. Out of that virtual tantrum was born a company (yet another one) and a subway lane that, at the moment, barely covers 2.7 kilometers.

LVCC Loop is the name of this idea that took shape in a metropolis of some 650,000 inhabitants. Its use, six years later, is anecdotal. And rather capricious: the route in question does not take up too many minutes of the driver’s time. It is more of an experience than a solution, but perhaps it fits in with what has come to be called the smart city.

With this nickname, the idea is to encompass mobility, but also inclusion and sustainability. Concepts that expand not only in relation to roads, but to a wide range of daily activities such as shopping or spending time on sports. In some places, the idea of the “smart city” has been replaced by the “15-minute city“.

A city that makes it possible to perform daily chores (work obligations, leisure, stocking up on necessities) without spending too much time moving around or despairing between waits or transfers, as happens in today’s metropolis, where distances and communications take up a large part of the day. In Madrid, for example, the average time spent commuting to work is 46 minutes, according to a study by the Moovit platform. This not only has an impact on personal well-being, but also on the environment. Not even teleworking, which “was here to stay”, has alleviated this.

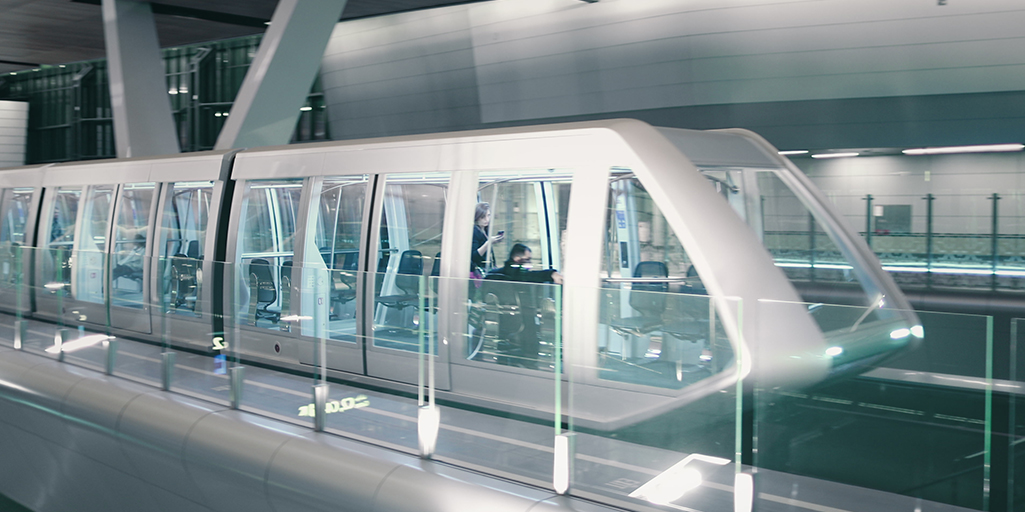

Now, not only are bike lanes encouraged in any city, but in this city, express buses have been proposed. A kind of urban AVE. They would be electric, with capacity for 100 passengers and frequencies of between eight and 12 minutes. In addition, only in the case of the capital of Spain, about 30 kilometers would be enabled with “traffic light priority” and away from the lanes used by other vehicles.

Those who proposed it likened this way of moving around to using the subway. And they emphasized the priority of public transport over private transport, in a trend that adds to the other main lines of action, such as reducing the number of cars in historic centers, increasing the frequency of trains and promoting policies in line with the demands of the planet.

Francisco Casas, a mobility specialist and founder of Emovili, a company that makes charging points for electric vehicles, believes that the progress being made is huge. “When we talk about smart cities, we see things that seemed impossible three years ago,” he says. One is, for example, closing cities to traffic. If we look back, we still see images of protests against the pedestrianization of historic areas. Today no one remembers them with cars and, better yet, no one wants them with cars.

“Regulation is already going to go in that direction, no doubt. And the big change will come with electric cars,” he says. According to him, there are three main obstacles that have paralyzed the massive expansion of this type of automobile. One is infrastructure, the lack of recharging points. Another is price. And finally, the battery. “This is limiting its spread, and we have had a few years without much progress, but there is already some momentum”, he explains.

At Emovili, as Casas explains, they are working with batteries that cover up to 1,000 kilometers. And with devices that not only require energy, but also supply it to homes. A revolution that is associated with the inverted pyramid that is being talked about in mobility circles. What does it look like? Well, at the base we should see private transport and at the top the pedestrian. Then come the bicycle, the public transport network, distributors and car-sharing.

Although, as María Eugenia López-Lambas pointed out in an article in La Vanguardia, “each city is a world”. “There are many types and sizes, and each one has its own needs,” stressed the professor of Transport at the Polytechnic University of Madrid and deputy director of the TRANsyT-UPM Transport Research Center. The challenge, she added, is to seek a shift towards more sustainable modes of transport, reducing the use of private vehicles. “The backbone of this is quality transport combined with alternative transport such as cycling and walking,” she said.

Tomás Ruiz Sánchez supports this: “Collective public transport must reach the entire urban area with a quality service adapted to each level of demand. Once improved, it must be well used to ensure its energy and environmental efficiency with low consumption and emissions ratios. The protection of pedestrians and the promotion of bicycle use are key to achieving efficient urban mobility.”

The professor at the Universitat Politècnica de València in Transport Planning agrees with his colleague that there are certain keys that can work, but also factors to take into account: traffic restrictions, pedestrianization or other measures will only be successful when the public transport alternative for the citizen is better in terms of quality, sustainability, accessibility and frequency.

And that means more than just inventing tunnels or offering buses without stops. We must broaden the transition to other forms of energy, forget fossil fuels, change outdated and polluting vehicles and, being more ambitious, change city layouts. It seems difficult, but there are examples from the past: think about the photos of streetcars and traffic jams in the main squares that now seem old-fashioned and that nobody misses.

_